MUSED: LA 2 HOU

MUSED: LA 2 HOU

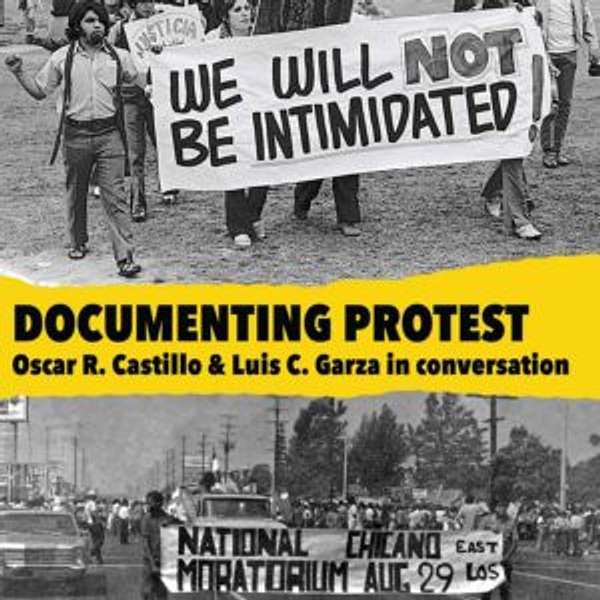

MUSED: LA 2 HOU | Oscar R. Castillo and Luis C. Garza | Documenting Protest

This special episode is drawn from a Zoom program organized by Riverside Art Museum and produced by CauseConnect on August 29, 2020 in support of The Cheech Center for Chicano Art & Culture. The online program featured photographers Oscar R. Castillo and Luis C. Garza...

The post MUSED Podcast: “Documenting Protest” with Oscar R. Castillo and Luis C. Garza appeared first on CauseConnect.

Check out more in-depth articles, stories, and photographs by Melissa Richardson Banks at www.melissarichardsonbanks.com. Learn more about CauseConnect at www.causeconnect.net.

Follow Melissa Richardson Banks on Instagram as @DowntownMuse; @MUSEDhouston, and @causeconnect.

Subscribe and listen to the MUSED: LA 2 HOU podcast on your favorite streaming platforms, including Spotify, iHeart, Apple Podcasts, and more!

Welcome to our second Zoom program sponsored by the Riverside Art Museum. Today we're going to have a discussion with Luis Garza and Oscar Castillo. The title of today's program is Documenting the Movement or Documenting Social Discord, Documenting History. If you know anything about the Chicano movement of the 60s, it was a turbulent time. At some point, it got even violent, not because Chicanos wanted it to be violent, but because the a reaction was violent. The Chicano movement has been described as being a renaissance, a looking back, a looking into our history, our culture, a rediscovery of music, a rediscovery of art, a rediscovery of historical figures. It was an examination of our status in society. We kind of looked around and despite serving with distinction in World War II, despite the creation of LULAC and MAPA and the GI Forum, We saw that our position in society was still very tenuous. We weren't allowed to live where we wanted to live because of redlining, because of a covenant that restricted certain types of people from buying certain property. We saw that the job market, that there was not just a ceiling, but a concrete wall that just did not let us go beyond a certain point. Chicanos were not getting educated. The superintendent of schools in LA County in one of the famous quotes said that educating Chicanos was worthless, was useless, was a waste of time, energy, and resource because we were best suited for stoop labor, meaning the only thing we were good for was working in the fields. So those were the kinds of things, the position that we found ourselves in. And when the movement started, it was a call, a call to action. And, you know, it told artists, go out and paint, go out and draw, you know, paint history, paint slices of life. Poets are supposed to talk about struggle. Photographers are supposed to document. Everybody had a role from the professor to the student to the comadre, everyone. It was a call for everyone to get involved. And tonight we have two fantastic folks who have agreed to talk to us about their efforts and what they were doing back early in the 60s. So I have Luis Garza and I have Oscar Castillo. It is my belief that, you know, we don't, that who we are today is based upon what we were when we were kids, what kind of family we grew up in, what kind of experiences we have. So before we get started, I want to know a little bit about you folks, because people may know your name, but people may not know anything at all, or people may know your image, but they may not know the name that's associated with the image. So I want you just really, as much as you feel comfortable, Tell me a little bit about yourself. So, Luis, I'm going to start with you. Where did you grow up? What kind of home life did you have? Were you in a, you know, complete family unit, mom and dad, extended families? What was the social economic condition of your family as compared to the social economic conditions of your area and of the times?

SPEAKER_00:Okay.

UNKNOWN:Okay.

SPEAKER_00:I was born in a war zone, 537 East 139th Street between St. Ann's and Brook Avenue in the South Bronx. My family is from Navajo, Vila Mexico, and the South Texas border areas. And in the mid-1920s, early 20s, part of the family migrated to New York City. Both my mother's side, Valdez, and my father's side, Garza, the brothers and sisters intermarried. And Little Colonia was established in New York in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was the opening of The Godfather Part II when they arrived. And they were looking for a compañero who had sent them a letter saying that there was work. in New York. So they took coastal ferry out of Galveston, Texas, and along the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, and up to New York City. They landed in 1922, thereabouts is what I estimate. And they found their way into 112th Street and Lexington Avenue and Little Italy. And they approached the superintendent of the building, and he told them, well, he's moved. He's gone. We don't know where. He says, but the apartment is available. And if you want to to rent it, we'll take it, they said. And it was a fifth floor, cold water flat walk up that they took. And that began my family from, Northern Mexico, South Texas, into the New York area. And I was born in the South Bronx in 1943. I'm 77 years old, or 77 years young. And that's a little bit of a brief with my family in terms of their journey. The family was Mexicano to the core. Papa didn't speak much English, apart from being able to tell you where to go if he didn't like you. And Mama was bilingual, and the family was Mexicano to the core. But outside it was everything else. It was Boricua, it was Italian, Irish, German, Jewish. I became all of them by osmosis in order to survive. We were the only Mexicanos in the area. But I never lost my sense of who I was as a Mexicano. And it certainly became more refined and defined when I arrived here in Los Angeles in the mid-1960s. And so I owe... Go ahead.

SPEAKER_01:Being from the East Coast, I now know where you get the accent from.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, it pops up more often when I'm with other New Yorkers and the Toity Toit and Toit Street comes out in me, you know? So yeah, the New York attitude definitely sticks with me. It's never left me, which has been part of my ability to survive. Being a loner in New York as a Mexicano, talk about being a minority. We did not have a network. We did not have anything to fall back on. on as most of the other immigrant groups in New York had. So it was quite distinct growing up, Mexicano. It was surreal. It was a Fellini, if you will. But it was one that I was quite proud of because it set me apart from everybody else. And as we moved from neighborhood to neighborhood, learning to survive amongst Italians, Irish, Jews, Poles, and Blacks, and Boricuas, and everybody else, you learn how to navigate. and that's what I've done all the way up to the present.

SPEAKER_01:Oscar. Yes. How much do you feel comfortable chatting about your

SPEAKER_04:background? Well, sure. I've rehearsed my, I've gone over my background. I've been thinking about it and all that. And although yesterday I expressed a desire to kind of keep that in the background, but I'll give you my spiel. I'm originally from El Paso, Texas. That's where I was born. My grandparents came from Zacatecas on my mother's side. And on my, no, I'm sorry, on my father's side. On my mother's side, as far as I can figure, they're all from the Texas, New Mexico area and I even suspect my great grandmother was full-blooded Isleta Indian. Her last name was Pompa or Pompas and apparently she was an orphan and she was raised by the nuns at the Isleta Mission. So and all of these things They, believe it or not, contributed to my interest in photography because as a youth, I was growing up in El Paso. We were very close family. We always lived in the close proximity to our grandparents and our aunts. We practically, just about everybody lived on the same block practically or within walking distance. And in some cases in the same home, same house. So we were very extended family. And my grandparents, all of them, always spoke Spanish. I never heard them utter a word in English, although they could if they were pressed. But my father was a professional. He actually was a career officer in the Air Force. And he always instilled in us to learn English and speak English. And my mother, up until we were teenagers, she always talked to us in Spanish. So we were always a bilingual family. And to this day, I love speaking Spanish, talking to people that speak Spanish. And I use that. That inspires me, the music, the culture, the familia. And that... that has helped me to develop a sense of community in my photography. And anyway, that in a nutshell. I mean, we did live in other places. I was fortunate to live in Massachusetts, in Bermuda, in Washington State, and eventually in California because my father was in the Air Force, so we traveled a little bit. And so I was always exposed to two cultures. But we moved to California when I was, My parents got divorced, so obviously we traveled different ways, but moved to California in the early 60s. And I was in high school at the time. I went to Belmont High School, where I played football, did the track stuff and all that. And then eventually went to college for a year, but was drafted in the Vietnam War. But I joined the Marine Corps instead being drafted, I said, well, I don't want to go in the Army. I'm going to join the Marine Corps. So I went into the Marine Corps and When I was in Japan, that's where I really got turned on to photography. I bought a camera. I self-taught myself. And even though before, when I was in high school, my mother had given me a little brownie, which I started snapping pictures with. And I'll go back to my previous statement that my mother created an album, which I still have. And it had images of all my family, my grandparents, people I never met. And I knew the story of the family. from that album, which I still own. But anyway, in here you asked, well, how did I get involved with La Raza newspaper? I think, is that here or in

SPEAKER_01:another one? Yeah, let's pause there. Luis, when did you come to California and how did you get involved in photography? Because you're in the East Coast. How did you wind up in Califas?

SPEAKER_00:Go west, young man, go west. After I got out of the service, I was in the United States Navy. And as a kiddie cruiser, I joined when I was 17 and a half years old. And I served out of Norfolk, Virginia on a naval destroyer. And that was 1960 to 63. And I saw... I saw the Navy and the discrimination in the South because we were based out of Norfolk, Virginia, and we were part of the blockade and ships that... escorted the Cuban rebels from Nicaragua and some old cargo ships into the Bay of Pigs. So there's a whole other history there, which is part of the political evolution of my thinking. But I wish I had picked up the camera then. I didn't pick up the camera until I came out to California in 1965. I got out here about a week or so before the Watts Rebellion. And It was a family of Puerto Rican Mexicanos who were living in Pico Rivera, who had come out from New York City. And so they put me up for a little while, and then I split and started making my way around. I didn't know anybody, didn't have any friends or anybody, so I was just cruising. Went to this college, went to LACC, and picked up a little brownie camera. I started taking photographs in 1966. I was going back and forth between L.A. and New are. You would transport taxi cabs, reconditioned taxi cabs, and you'd drive them four or five days. A bunch of us would jump in the car and pop Benny, smoke a couple of joints, and we'd travel east and west. And you'd drop off in Los Angeles, everybody would go their own way. So that's how I did it for a little while. So

SPEAKER_01:was the Brownie camera, was that the camera of the day, or was that the amateur camera of the day? No,

SPEAKER_00:that was the beginning's of my interest in photography. It was short-lived, and then I picked up a Pentax camera, 35 millimeter, and I started just photographing on my own with no direction to roam, as Bob Dylan would say. I was a rolling stone. So I was broke. I was destitute. I didn't have nowhere to turn, and a friend of mine from school, who was a social worker, said, let me introduce you to a man that may be able to help you with a job. That man's name was Ed Bonilla, who was the director of NAP, Neighborhood Adult Participation Project, which was part of the Great Society of Lyndon Johnson. And it was a storefront on 18th Street and Broadway in Lincoln Heights. And I went in to meet him, and I had my camera around my neck. And he looked at me, and he was stroking his mustache and his goatee, and he had on shades. He was... He was old school Chicano from the barrios, but he was the director of NAP. And he said, so... you need a job. I said, yeah, I need a job. He says, and you're from New York. And I go, yeah, I'm from New York. He goes, uh-huh, okay. He says, you're Puerto Rican. I go, no, I'm not Puerto Rican. I said, well, yeah, I'm Puerto Rican by osmosis. And I'm Jewish, I'm Irish, I'm Italian. I'm all of those things that I grew up with in New York. I said, but my family is from Mexico. And he questioned me a little bit more. I was getting a little bit exasperated. And he says, and you need a job. I said, yeah, I need a job. And he says, and he strokes his goatee and he says, a Chicano from New York. That's an honor. But I had never heard the word Chicano. Oh. I mean, this is my first entree. This is my first dance. And so I think to myself quickly, I said, Chicano, Mexicano, there's no difference. I said, yeah, I'm a Chicano from New York. And he goes, you got the job. And I go, all right, great. What's the job? He says, you're going to organize the people. I said, how do you do that? He said, well, you show up tomorrow, you bring your camera with you, and we're going to start. And that next day, he parachuted me right into the middle of the whole emerging Chicano movement. He introduced me to Father Luz, Joe Raso, Raul Ruiz, Eliseo Risco, a whole bunch of sub-people, union members, union organizers, the whole beginnings of the Chicano movement. Is that 66 or still 65? That's late 66, 67. Okay. And so I'm on a fast track. And... The blowouts take place in high schools, and I begin photographing. But now I begin photographing with

SPEAKER_01:a purpose. Okay, let me pause you there. I'm going to go back to Oscar. Oscar, so you got the Brownie camera in 1966. You said that you went to Japan, and that sparked your interest in photography. Why the little Brownie camera?

SPEAKER_04:Well, no, the Brownie was when I was in high school. That was more like an Instamatic. I think it's a different camera, but similar. A Brownie was a larger camera. Instamatic was a little cassette camera. But when I came back from Japan, I had already gotten the bug to take pictures and I had quite a background already in self-taught photography. And when I came back, I worked for the phone company for a little while and decided to go back back to college instead of working a real job. And anyway, I started at Valley College and I met a lot of the, at the time it was called UMAS. So I got involved in, you know, when you go to college, you want to get in with a fraternity or sorority. And this was the Chicano version of a fraternity or sorority, because it was both men and women. And at the time, I got involved with the UMAS and they were involved at the time with electing Tom Bradley. He was running for office. So anyway, I got involved in political, you know, events. And I think that was in 69. And that was actually the first time that I was involved in, That was when the LAPD raided the Panthers headquarters in South Central Los Angeles. So a friend of mine said, come on, let's go down. I mean, I hadn't heard about it. My friend had heard on the news. She said, let's go down there and see what's going on. So I went down there, took some photographs out of the window as my friend drove the car by. All the shooting had finished, so we just drove by and took some pictures, which are actually going to be used. It's amazing how things take a long time to gel, but those pictures are going to be used. by a lady who works with the African American Museum. And they're doing a project on South Central. They're gonna be putting these kiosks. So they're gonna be shown on these kiosks in the street. But anyway, beyond that, I went on to Cal State Northridge, which at the time was San Fernando Valley College and got to be known because I was always carrying my camera. And I started taking a Chicano studies and I had a dual major. So I was fortunate to meet Rudy Acuna, who is a well-known historian. And he was in the process of writing some books. So he said, how would you like to be the photographer? I said, sure, absolutely. So it was a paying job. It was my first paying job as a photographer. And he gave me a script and I went out and I shot the pictures and it was published and it was used throughout the state of California, seventh through 12th grade in social studies. So from then on, I went on, I took a class in, It sounds like I'm bragging, but this is my history. I took a class and it was a group. We did a newspaper on campus. It's called El Popo. And the instructor was a graduate student named Frank DeLomo, who later became a senior editor at the LA Times. And I think the class advisor was Raul Ruiz. And he invited us to go visit the La Raza newspaper to see the facility. So I said, sure, why not? So I went down there, and they had a dark room, and I was interested. I mean, I really had the experience doing a newspaper, so I got involved with them. Here

SPEAKER_01:with Ed Bean.

SPEAKER_04:I'm sorry, what, here?

SPEAKER_01:Yeah.

SPEAKER_04:um it would have had to be uh 70 because i was there i mean this was very fast track between 69 70 it was all happening like boom boom boom right after the other and uh that's how i got i was there for some of the events which were the the moratoriums the the the catholicos which happened i'd have to check my records but it's either 69 or 70. i was in 69 and then 70 was the moratoriums And I was not a permanent fixture at La Raza, but I was a kind of a visiting photographer. I wasn't involved in the policy setting or anything. I was just taking pictures. And occasionally my stories would get, not my stories, but my photos would get published. And especially the ones from the moratorium. And then I went off and worked for a semester. And right after the moratorium, I went to Crystal City, Texas and spent a semester there. with Jose Angel Gutierrez. I came back and published, augmented one of his articles with photographs that I took at the time. But anyway, from then on, it just kind of snowballed. I kept getting, I met people like Irene Blea later on in life. And I'm very fortunate to work closely with a lot of scholars, historians. And so my work has been kind of snowballing and I'm getting a lot of people, well, and people ask me for my historical things. And Although I do other things, I exhibit as an artist, but the historical things are the events, where the art is like the cultural things, working with, I've worked with the Teatro Campesino, I've worked with musicians, I've got to meet El Chicano and Daniel Valdez, and a lot of other people. I was fortunate to meet and photograph all the great, like Corky Gonzalez, Tijerina, Bert Corona, Dolores Huerta, and work with people like Mayor Bradley after he was elected. And so over the last 50 years, I've been a professional photographer and worked in it in many aspects, commercially and historically and for fun. Okay. Luis.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah, that's real. I think we could do a two-hour show just on each one of you alone. Luis, so... In 66, you meet Mr. Bonilla, and he introduces you to all these folks. Was La Raza newspaper already in existence, or was it in its formative stage?

SPEAKER_00:La Raza newspaper was in existence. It started in September of 1967. I come aboard a couple of issues later. And the lifespan of La Raza is 67 to 77. And so the... The newspaper transitions into a magazine format in 1970. So we go from a 12-page Gestetner printout, bilingual, with the use of some photographic work and cartoon work and things like that. And it's out of the basement of the Episcopalian Church of Father Luce. And then we transition in, well, we have to move several times. So when Oscar comes aboard, as he said in 1970, that's when we had made a move, a major move, and practically a final move to City Terrace. And that's where we create the darkroom. We build it from scratch. We outfit it with the latest printers and enlargers. And, you know, we have it all set up. It's a professional run darkroom, which we created. I have learned how to do that with the work that I had done with another a photographer who mentored me for about a year's time. So I learned the basics of darkroom work and building a darkroom and mixing chemicals and all of that, which is what we were doing with each other. We would pass on the information. We would educate each other. We would train each other. Many of us were self-taught. Oscar and I probably are the... Debra Weber is another one who stuck to camera work and it became part of our professional lives. Most everybody else, you know, did it, picked it up, dropped it for the most part and had other gigs. But for us, it became primary. And for me, it became pathway into the larger media world because I transitioned from La Raza in late 72, 73 into documentary filmmaking. ABC, NBC, other television stations. So a pathway was set for me. Photography created a foundation for me and a base for me from which to grow. Go

SPEAKER_01:ahead. Well, what was it like, though, in those early days of La Raza meeting, you know, Eliser and Jose and all those folks? What was it like? I mean, what was the energy or lack of energy like, you know, joining those group of people?

SPEAKER_00:Well, it was formative. It was evolving. It was, you know, I think we were all learning at the same time. And it was meeting a variety of people from to the academics, to the professionals, to writers and poets and artists of all stripes who would come into the offices, especially there at City Terrace. It was a hotspot for gathering. And so It was a salon. It was like 24-7 practically every day. And it was also the base of a lot of meetings and conferences and strategy meetings and how do we put it together? What's our next move? And then printing and working on a magazine that is now 60 to 80 to 90 pages that goes from a local to regional to a hemispheric publication. And so the scope of the magazine and the content of the magazine expands tremendously. So you're stepping into an environment where we're all creating. It's a creative process. It's an organizational tool primarily, but it's also a creative process for all of us. We have very little outlets for our talent, for our desires, for our political and cultural aspirations. So La Raza becomes a fountain for that.

SPEAKER_01:So did you see your Did you see yourself as purely a person who shoots film, or did you see yourself also as an activist, somebody who was involved in organizing, prompting, you know, those kinds of things?

SPEAKER_00:I saw myself as a photographer. I was not... At that time, I was... not vocal. I was not a speaker. I was very shy. I spoke through my photographs and my language was beginning to become more refined as I learned the craft of photography. I studied other photographers from Manuel Alvarez Bravo to Cartier Bresson to Akira Kurosawa to any number of cinematographers and photographers of name, Dorothea Lange, etc. And I go to the museums and study portraiture. I study the works of artists from the past to the present to see their composition, their framing. I taught myself the craft. In order to dominate and understand the craft, which is technological, I had to understand how it worked. And so I involved myself that way. And that takes hold of my photography. As you begin to study my work, you begin to see the evolution. You begin to see the evolution of each of the photographers of our fellow colleagues who are involved. Some evolve, others don't. Some always take out of focus shots and others take sharp shots. You see what I mean? So it's a process and you have to engage in the process. It's a discipline that requires constant work.

SPEAKER_01:What were some of the earliest events that you shot? You know, Ed Bonilla gave you a job and he said, I'm going to send you out to, you know, work with the people. What were some of the early events that you shot?

SPEAKER_00:Well, the first events was the blowouts in the school and the walkouts and the Board of Education and the sit-ins and Sal Castro. So within my files, both at UCLA and at home, are hundreds and hundreds of photographic images from that period of time. many of which have never been seen before. That's one. And then you've got to remember, and I'm always amazed at how on a weekly, on a daily basis, organizing was going on, demonstrations were going on, whether it be educational issues, immigration issues, police brutality issues, war issues, any host of other subject matter. that were unfolding. And whatever organizations took it on or whatever combination of organizations that banded together to bring it to the forefront, it was constant, much like what's going on today. When you look at what's going on today, it's constant protests. It's constant demonstrations. It's constant vocal outrage to the systemic oppression that's going on. Well, it was the same thing back then for us. Now, the civil rights movement in general was going on throughout the country, throughout the world for that matter. You know, Vietnam War brought an international uprising, if you will. And you begin to look at it from that point of view. I didn't come into this politicized. I came into it with a sense of politics from my childhood with my father. who always used to curse out the pinche gringos, metiéndose donde no se deben de meter, you know? And so I had a sense of it. So the formulation, though, and the sophistication of it is a slow evolvement as I become more and more involved and more engaged. And I begin to start connecting the dots. And photography helps do that for me. So photography gives me a base. It gives me a foundation. Un razón de ser. That was the era of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, and I was into all of it. And so trying to find my footing and say, okay, who am I? What am I in this world? What's my purpose? What's my razón de ser? Well, photography became that. The Chicano movement became that. I was reborn. Fue un renacimiento para mí. Right.

SPEAKER_01:Oscar. Yes. So in 1970, you get introduced to La Raza. Do you cover the first two, what I call pre-moratorium, pre-major moratorium marches? Did you cover any of those two?

SPEAKER_04:Yes, I did. I covered the one which was started at the Cinco Puntos at the Veterans Memorial there in Boyle Heights, went down to, I think it's called, I forget, Obregón Park. And then the one moratorium in the rain, I covered that one. Okay. And then I covered those. Those were, I mean, I did those independently. And then I really didn't hook up with La Raza people until the moratorium. Okay. Did

SPEAKER_01:you cover that at the behest of La Raza or were you still independent? Which one? The last one, the major one.

SPEAKER_04:Well, I always considered myself independent because I was not official. I don't know what the protocol was. I don't know if you had to get sworn in or whatever. I say that jokingly. But I know everybody was volunteer. And I would come and go. And they used to have staff meetings. And I attended a couple. But I didn't really get assignments per se. I don't know how that worked. I always considered myself a freelancer, but I did, when I left, I did leave my files on that one moratorium with them. And also the event, which was called the Marcha de Justicia. And those images have been, safely kept for over 40 years in a vault somewhere, but recently were released and were then documented and archived at UCLA. So then they were able to come out to the public, which they would come out and, you know, to see the Day of Light. But

SPEAKER_01:that wasn't kind of... In preparation for the Chicana Moratorium on August 29th, what were the expectations? What was the buzz of the community? What was, you know, what were people talking about as they were preparing for the march?

SPEAKER_04:I don't think anybody expected the outcome. I think everybody was very up and very, you know, very festive about it. Although it was a kind of a negative subject, you know, the Vietnam War and protesting against the, you know, um lopsided you know, death figures and injuries to Hispanics versus what we're calling Chicanos versus the non-Hispanic. I think in Vietnam, it was extremely high, maybe as high as 20%. I have the, I have the, but anyway, they were hoping to, I mean, I feel, I didn't really have much contact with say the Brown Berets or the organizers, but in general, I was in that, you know, circle of people that were, that that were, activists at the time. But I think they wanted to just basically bring this to the forefront. And I think one of the problems was that the media did not cover our point of view or the Chicano point of view. And I think it exists to this day. I don't think there's been much change. They do cover a kind of token Chicano or Hispanic events, but they ginger coat it. And it's very, very, you know, lopsided. I hate to compare it, although what's happening now is the Black Lives Matter, but minorities are always thrown in a bad light. But anyway, your question was, what were the goals? My goal was just to take pictures and document some of the things that were happening.

SPEAKER_01:So where did the march, what was the starting point of the march?

SPEAKER_04:The march started at a point which is on 3rd Street in East Los Angeles, 3rd near, I believe it's Dittman, which is now they call the East Los Angeles Civic Center. But that's also the point. There's a park there, and that was a staging area. And they walked east towards Atlantic. and then south on Atlantic to Whittier, and then west on Whittier to Laguna Park, which it was called then. And I marched along with them all the way and took pictures and became aware that, of course, this was a standard procedure, but there was many plainclothes policemen. Also, there was, you know, clothed policemen.

SPEAKER_01:There appeared to be a variety of different ages involved in this march. Did you

SPEAKER_04:notice that? Right, right. In some of the, I mean, there was people there, there was mothers carrying children, there was older people, there was a lot of college students. They have these, you know, very conservative people like the Mexican-American political association, MAPA. And so there was a lot of support from people coming from from as far away as Texas. This was one of my schoolmates at college, Abel. I forget his last name, but he caught him there sitting with the poster against the war in Vietnam.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah, our fight is in the barrio, not Vietnam.

SPEAKER_04:Yes. And then this was on Atlantic. And you can see, obviously, it says Nixon, no, Chicano Sea, a pass. So there's... This was on Atlantic Boulevard.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah, these look to be like 10, 11, 12 year olds.

SPEAKER_04:Yes, yes. They seem to be preteens or early teens. And there's a lot of support from the younger people. And then this is a brown beret. Well, I don't know if she's an actual brown beret, but she's wearing a brown beret and a brown sash and helping carry the banner. And this was on Atlantic. And then we have the other group. This has gotten a lot of usage on book covers, a couple of book covers and books. But this is a, you know, late teens to early 20s, and an older man there on the right wearing a sarape vest. And then they got the guy with a couple guys with the bare chest, and then the women in their coplorico blouse and more contemporary. So I like to show the cultural, the cross-cultural within the culture. And there's the mom with her son, and maybe she's a grandma, I don't know. But there's a little boy there. there, a girl in the back with a flag and her husband pushing their baby. This one is a lady with her child.

SPEAKER_01:And you notice the UFW flag is prominent now during this march. I mean, there were a couple of slides where you saw either some handmade posters or actual red flags with UFW. Was that symbol prominent throughout the entire march or was it isolated?

SPEAKER_04:No, I think it was prominent throughout the march because there was a lot of cross support. I mean, people not only supported the anti-war movement, but they supported the farm worker movement and the rights of the farm worker for equal pay and, you know, living conditions. So Cesar Chavez was very, very well supported amongst the activists at the time. So I think, you know, people were doing, you know, they were... doing double duty. They were supporting the anti-war movement and supporting the farm worker movement. So I think those two things went hand in hand. And then here you see a tale con cures. So people are also both adding cures, which was apparently, you know, in bad with the community. You have a youngster there with his dad and the lady in the back, you know, everybody very, very up. And there's a reference to Che Guevara in the background because there was a support for Che especially and for the liberation of Cuba. So there was a lot of– there was multiple things happening. And here you have the reference to– somebody being killed in Vietnam, Sanchez, the name of a fallen soldier over in Vietnam.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah, some of the bad parts about coming, you know, fighting in Vietnam and coming back is that there were covenants that did not allow Chicanos to be buried in white cemeteries. Yes, yes.

SPEAKER_04:I know when I was in Texas, there was a... I think that the GI Forum came about because of that, because they would not allow somebody from the World War II to be buried. But in Crystal City, I have pictures at a Spantion Benito Juarez, which was created because they wouldn't allow Hispanics to be buried in their Anglo cemetery. And this is after the violence at Laguna Park. And the line of deputies, they're clearing the street. And after a while, I mean, they would pretty much leave the photographers alone. But then after we published photographs, I had to do some fast running on a couple of occasions. The gentleman, the deputy on the right, holding the tear gas weapon, that's the one that shot Ruben Salazar. And then the one in the middle is carrying a gas generator, which was used to spray people to clear the Laguna

SPEAKER_01:Park. So the guy on the right is the actual guy that shot the canister into the Silver Dollar Cafe that killed Ruben Salazar? Yes,

SPEAKER_04:he is. If I remember correctly, I have a closer up shot of him, but it hasn't appeared yet in the missing negatives from the Rasa magazine. But this was at the Laguna Park. And there he is again right there. And this is right there in the adjacent street. They were going, they were shooting and they were going after people right in their front yards and shooting pure gas. And as I say, at first they left me alone. Maybe they thought I was a press photographer, but later on, on the 16th of September, I was actually chased on a couple of occasions. by very aggressively by deputies. I have to make a note, kind of apologizing for the quality of the photograph. Normally we would develop our own film, but in this case, somebody else developed it. So I'm not complaining, but it's less than, you know, less than a quality, but it hits a lot of grain, but still it gets the message across. But when you develop film, you have to be aware of temperatures and agitation and all that kind of stuff. And some of the people, as Luis said, I mean, some of them were mentored by other people and some people took it on themselves to process their own film. And if there was any... any handy. I mean, there's something that hadn't been processed. They would, you know, they would do us a favor and process it, but this one I did not process.

SPEAKER_01:So this appears to be the park after it was cleared.

SPEAKER_04:Well, it was in the process of being cleared. I think the main group of marchers are gone, and you can see all the litter And they're still trying to maintain the ground that they had

SPEAKER_01:already cleared. There's also reports of several people being beaten up with batons.

SPEAKER_04:Yes, yes, yes. I mean, there were some videographers there. There's evidence of people being, I know one woman in particular, Viviana Chamberlain, it shows a depth. She was standing in the middle of the park and he came up behind her and just gave her a tremendous blow to the back of her head and she just kind of dropped. But that's the kind of things that were happening.

SPEAKER_01:Now, here is an LA Times. And whose photos did they use for the LA Times coverage?

SPEAKER_04:Well, the top two and the bottom left were by Joe Rosso and Raul Ruiz. They were both together in front of the silver dollar. The one of the deputy over here on the bottom right, that's mine. And then inside they use other people's. But we didn't claim personal credit. We just gave it to the magazine.

SPEAKER_01:So, Luis, let's go to you. So you were not at the Chicano Moratorium because you were attending to your mom. Tell me, what did you know about the planned events at the moratorium? And then when did you come back and what did you see as the aftermath of that?

SPEAKER_00:I had left Los Angeles several days before the moratorium. My mother was undergoing a cancer operation. We did not know if she was going to survive. So it was a difficult decision, but I had to be with my mother. So I flew back to New York to attend to my mother and see that hopefully she would survive, which she did. And she outlived the doctors, which after they gave her a week to live or a day to live or a month to live, and she lived long after the doctors. Thank you very much. doing the work necessary to start printing up images and prepare the special edition issue that came out with the images that Joe and Raul took of the silver dollar. And those images that you saw in the LA Times, as Oscar pointed out, were from... from Raul and Joe, who did not know, here's a side note, that they did not know that Ruben Salazar was inside the Silver Dollar Cafe. They had seen the gathering of the sheriffs in front of the Silver Dollar, and so they just made their way through the crowds and the police sheriffs to the Silver Dollar, and they positioned themselves on either side of the corner and started photographing, not knowing that Ruben Salazar was inside. They did not until later on that evening when the news came out saying that Ruben Salazar had been killed. And that's when they looked at each other and they said, we've got to develop the film and realized that they had captured that moment. And so that moment rings and resonates throughout our community, resonates within national media, and goes international. So La Raza magazine, through Joe and Raul, capture and document a historic moment that nobody else captured. And so La Raza gets international recognition where nobody else was there. No other photographers were there that captured that imagery. It was just Joe and Raul, which is ironic because that catapults La Raza magazine into more prominence. And it gives validity to the work that we were doing in terms of the pushback, pushback of the information, the information the contents and the imagery and the editorials and all the work that was contained within the magazine. So we take on an added aura within the CPA, the Chicano Press Association, which is made up of several hundreds of newspapers throughout the Southwest up into the Midwest. And so we are predominant in terms of being photographically driven. And as Oscar was saying, in many cases, the photographers never got photographic credit. That was just part of the way we did things back then. Unless you had a photo layout that was specific to you. Manuel Barrera had that, I had that, and a couple of other people. Maria Marquez had that. We tried to do sections for the photographers to get the recognition And the only recognition that people received, because it was non-paying, it was all volunteer, was at the end where you would get credits for participating, whether it was just for that publication or whether you were there constantly. It was all volunteer work. No one got paid. So it was a love of labor. And people came and went. It was a revolving door. But there was a core group of us. And amongst the photographers, there was a core group of us, which led to, and that's a whole other subject that I'm sure you're going to jump into when we put the La Raza exhibition together. So it's representative of the the work that we did back then. And there's a lot of what we call staff photographers because we have not been able to identify who took the photographs, which is part of the task that we're undertaking still to this day now. I've counted about 35,000 to 40,000 images. We at first thought it was like 20,000, 25,000, but I've been through the... through the collection several, close to a dozen times because I had to curatorially to put the exhibition together. And so it's taken me all this time to become familiar with each of the photographers and their work. And it's truly a deep sense of respect that I have for my fellow colleagues and the work that they have done. So what was the atmosphere like after the moratorium? The atmosphere was tense. It was extremely tense. We were under constant surveillance. The office got busted into several times by LAPD. You'd leave the office and you'd have a squad car following you. And you wouldn't know if you got home on that. Sometimes you'd be stopped, you'd be harassed, or you'd be picked up. And that was part of it. Like Oscar was saying, there were times when you... you had to run. And there were more than many times that I had to run with my camera, jumping fences. hiding in houses and trying to get away from police that were chasing me and some of the others. We were identified. They had us. They had us pinned. They knew who we were. They would harass us. They would park outside of our offices. They'd come in. We had a first name basis with many of them. LAPD, undercover, whatever they were. You always smelled them. You always knew who they were. And in fact, we used to tell them, you know, you should give 10% to the cause. And they would say, what cause? They say, cause you got a job because of us, that's why. Otherwise, you'd be washing dishes down at Skid Row. That's right.

SPEAKER_01:So that was the reaction of the photographers. How did the community react to the aftermath of the moratorium?

SPEAKER_00:Well, it... You know, it's like what's happening now. It doesn't dampen the spirit. You know, you just get so enraged with the response from the powers that be in government and within the LAPD and within the sheriff's department or within whatever, FBI, CIA, of todos, you know. I mean, we're on file. They had us on file. Shoot. Outside my home, they'd be parked and they'd come up to the house. They'd talk to my mother about me. We went through a lot of harassment. It was constant. It never stopped. So were there more marches and more protests after that? Oh, yeah. Yeah, it was constant. That's what I'm saying. I'm truly amazed and respectful of how the people turned out. The more suppression that came, the more outrage that was done and weekly, the constant demonstrations. So many, I can't even identify any number of them. You know, some of them stand out and many of them don't because I just lost track of them. But we try to photograph as many as we could. You know, not all of us were there at the same time. That's one of the things that we're doing with the archive is that we look at the period of time that the photographs represent. Who is it that... specifically was there and who was not there who was part of the magazine at that time and who was not part of the magazine so it's a process of tracing each of the photographers and their history with the photographic work that was done so this is where you begin to narrow it down to okay this batch of photographs belongs to this photographer we concede you know before

SPEAKER_01:we talk about the January 19 um 71 uh protest there was a question oscar um yes how are you earning a living i mean you're a photographer is did you have a day job

SPEAKER_04:Well, back in those days, I was a full-time student from 69 to about 73. And I was living on the GI Bill. I was getting a stipend for military service, but I did have a job in a drugstore. I was delivering prescriptions. And then I was a counselor at U.S. at the university i was a peer counselor for a little while and then actually i got a job with the with the state of california working in the because of the chicago studies major kind of qualified me for social studies major and i i was recommended for a job with the state of california for for a while uh with the department of unemployment And then after that, when I left college, I worked for a while with Jesus Trevino at KCET as a production assistant and worked with him and Luis Ruiz. And that's how I got to meet a lot of people like the Teatro Campesino and other political people. But that... after i left there i left kct i went to work for for cal poly pomona with vera who's in the audience here i was there for a little while at cal poly pomona as a production assistant and then i went on to cal state la as a as a as a production um uh consultant but but all the time um I had photography as a free, I would do it freelancing. And I never really got a full-time job as a photographer until 1986. And I worked, and that's getting way, way, way over this side of the auditorium, but I worked for 20 years as a city photographer for the city of Pico Rivera. So I got to work with the city in all capacities. I would document all the events, all the political stuff, city council meetings, And I got to meet, it's ironic, but I got to meet Sheriff Baca when he was sheriff at the time. And anyway, that's another story, but... I worked there for 20 years and I retired. And so I'm now retired and I still do freelance work. But I never, in terms of the political stuff, it was all out of my own, it was on my own. I was never paid to do that stuff. It was there just out of a feeling that I needed to do that. So it was not like somebody said, here, go photograph these demonstrations. It was all on me. So-

SPEAKER_01:Luis. Yeah. Yes, sir. So Luis, did you have a daytime job or did you just earn money off your photography?

SPEAKER_00:No, I've never earned money off of my photography until recently. Actually, only over the past decade. It was a love of labor for me. beginning with La Raza magazine. But then I segued into documentary filmmaking and doing a show called Reflexiones for KABC TV. It was a half hour show that we used to do every other week. We would alternate with a black theme show called I Am Somebody. And that was the time when the doors were kicked open and we were allowed in to do public affairs programming. So that was my introduction into the television media, but it also introduced me to the lack of diversity within the television media and the larger media in general, to which Oscar referred to earlier, which is so true to this day. I mean, we have more coverage, we have more representation, but nowhere near the coverage and diversity media coverage that we should be receiving for the portion of the population that we represent.

SPEAKER_01:Especially since we're 49%.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So you got to consider that when I entered into 1972, mid-72, late-72, I entered and started the half an hour show. Jesus Trevino was the only other one at KCET. And then there was a couple of newscasters, Henry Alfaro and A couple of others, their names escaping now, who had... more or less a sit down, you know, two cameras set up Q&A in studio. I took the approach of wanting to make cinematic programs and we'd go out and we'd shoot and we'd create a story. And regardless of what the subject matter was, which ironically for me started, my first show was Ricardo Chavez Ortiz who hijacked the airplane from Arizona to LA. And the very first day that I come in to start work on this program, Ricardo Chavez Ortiz hijacks the plane, and that becomes my first story. John Noriega has my historical video files over at UCLA. He managed to salvage all of the programs from Reflexiones. There are some 30, 40 programs that I did, along with several other colleagues, Susan Dracho, Tony Rodriguez, David Garcia, and a couple of other people, Andres Chavez, who's passed away but we did a body of work for better or worse you know we gave it our best shot and we did it cinematically we did it to tell a story and often times we'd create theatrical stories Flores Magón or the indigenous movements AIM and Boricuas and Prop 22 and any number of other subjects that were popping up at the time so that become a further escalation of my work within the media and that introduces me to any number of other people within the larger media. That's how I come to meet Margot Albert at Plaza de la Raza and I begin to start working with her at Plaza de la Raza as a cultural arts center and one of the first that just celebrated its 50th anniversary. So I become involved with Plaza and with Margot and we're doing one hour specials, we're doing theatrical work, we're doing any number of projects she opens up the door and I come in and she throws me into producing directing writing and doing what I've never done before but what's new I always seem to be parachuted into these situations you know so you take it you run with it and you do the best you can

SPEAKER_01:isn't it amazing how successful one can become when you stumble through life because nobody has done it before. No one has shown you how to do it. You just happen to be at the right place at the right time. And you work your way through it. You may not have the necessary skills, but you pick them up, you adapt, and then you go forward. I mean, that seems to be a whole group of people There's a whole group of Chicanos that if there was a

SPEAKER_00:description of their life, that would be it. Well, yes, absolutely. And it certainly applies to me. After my father died, I brought my mother out to California, here to Los Angeles, and she lived with me for a while. And she'd watch me working late into the middle of the night, and she'd stop at the kitchen door, and she'd look at me, and she'd go... You work so hard, but you don't make no money. You should become a dentist. They never run out of teeth. I'd say, thank you, mom. Thank you, mom. And I think to myself, damn, is it too late to become a dentist? It's too late. It's too late. Exactly. Exactly. My path was set, you know, for better or worse.

SPEAKER_01:So let's go back then. So the There's a series then of protests and just daily outrage at the killing of Ruben Salazar and the other two individuals who were killed at the Chicano moratorium. There was a march in January of 71 that you documented.

SPEAKER_00:Yes, the catalog comes out post-exhibition, which is ironic, and I think serendipity. The exhibition ended after a year and a half run from 27 to 2019, February 10th. And the catalog just came out late January, February. I haven't done to go revisions and rewrites and all of the things that go with putting this thing together, which actually turned out to be a good thing because it's revived the exhibition and keeps the exhibition alive in the memory of people. And it has, one, And, um... Just a couple of months ago, it won the IPP International Publication Book Awards in the area of U.S. history, which according to John Noriega is a first. It's never happened for a museum catalog to do that. And for UCLA, it was kudos. And recently, over the past couple of weeks, it's been nominated in four categories by the International Latino Book Awards, another first. It's never happened for a catalog and to have four nominations for one book. So it speaks to, well, it speaks to the good work that was done. And, you know, kudos to all my fellow colleagues and all that were involved with putting the catalog together, from UCLA Chicano Studies to Audrey to my fellow photographers. this We Will Not Be Intimidated is taken at Laguna Park January 31st 1971 Oscar was there as well and a few of the other photographers This image, it's early morning. You can see the fog in the background. And there's just this line of students just marching forward. And this is just one of a series of images. You've got to remember that every image taken, there's before and after images that were taken, or at least as many as possible. Sometimes it's just a one up. This is the beginnings of the renaming or the desire to rename Laguna Park, Rubén Salazar Memorial Park. The Teatro Campesino Calaveras are in the background, and they have just given a presentation. They're marching along with all the fellows, marches towards Laguna Park. And again, this is just a series of photographs. It's several rolls of film that I took. on this

SPEAKER_01:event. Is that Daniel Valdez on the left-hand side in the white shirt?

SPEAKER_00:Yes, that's Daniel. That's Daniel. So Teatro Campesino came in, and this is at the park itself, part of the demonstration. And this is... again just a part of the series but the use of the peace sign and the very creative ways that the young women phrased and made their posters and their banners and the dedication and the seriousness of everyone that was there, the commitment. And there were thousands, there were thousands all over the place. And this was la marcha por la justicia, and this was against police brutality that was taking place, because they were knocking us off. If they got you and they took you to jail, you weren't sure if you were going to come out of jail. There were so many quote-unquote suicides that took place.

SPEAKER_01:What I love about this photo is the youngsters. I mean, you know, Chicano students, high school students, college students always play just a big, gigantic role in the movement, whether it be the blowouts or everything else. And as I look at this photograph, I only see maybe three adults, three people who I, you know, can... can guess are over the age of 18, but everybody else seems to be just like youngsters and students, man. It's just, it's wonderful, it's beautiful.

SPEAKER_00:Well, this one speaks for itself. And again, it's so applicable to what we're going through today. Don't make a joke of your rights. Right. You know, past is present and is future. The commitment that people put themselves on the line, that they were willing to take the body blows, that they were willing to fight back, that they were willing to step up and organize. And this was also, this is the beginning of, as Oscar was pointing out to his other image of August 29th, there's a militarization process that's going on, and you can see it. And here you have a BAR building Vietnam weapon, tear gas canisters, and they're loaded. They're ready. And it's just all over the place. And they're coming after us. They're live rounds. There's no pellets. There's no rubber bullets. You know, no.

SPEAKER_01:It's amazing to me that 50 years later, we get the same... We get the same... We get, you know, you ask for rights, you ask for something, you ask for equality, you demand change. And the response is not, hey, let's sit down at the table and try to work this out. The response in 1970, 1971 is, to 2020, the response is the same, which is overhanded response. And this image can be transplanted to what's happening in a variety of different states in the military Humvees, the military outfits, the military weapons, the AR-15s. It seems that we haven't learned in 50 years how to sit down at the table and talk about differences and how to reach an agreement about change. It seems that we're always dealing with this response right here. And I think that this image and even this image just speaks to the response that we continually

SPEAKER_00:get? Well, it goes back further than just 50 years. A colonial empire does not negotiate with its subjects. And much of the literature is out there. We are subjects. We are colonized, all right? The pushback that we see going on today dates back to the foundation, the founding and expansion of the empire. That's just fact. That's- Texas Rangers, California Rangers. Absolutely, absolutely. You're negotiating, you don't negotiate with the empire. The empire doesn't negotiate. And if you do, you negotiate on their terms and their terms are brute force. This is Gustav Montag, the killing, the death of Gustav Montag. This is a series of photographs. The brown beret there is a medic by the name of Richard Soto who has established, he comes out of the Sakara area. I don't have the information in front of me. There's a series of shots where they carry the body of Gustav Montag. And they lay him down. He's dying. He's just dying. And they're waiting for an ambulance, which takes forever to come. And the irony of it is, when you go to the next image of Raul placing the flag on him, this is at the site where he gets killed. And Raul is placing the Mexican flag on him symbolically to identify him. as Chicano, whom we thought was Chicano. But we came to find out later when the police said that he was not Mexican-American, that he had a Slavic name, so therefore he must be a communist agitator who came to stir up the masses. And then they recanted and pulled back that and said that, no, he was just a Jewish kid from the Boyle Heights community area who had come to observe. And he caught a spray of shotgun pellets that ricocheted off of a wall right next to him. And that took him out. But the thing about this photograph also is, which always strikes me, is that if you look at his feet, his shoes, his feet are sticking out of the soles, both soles of his shoes. And I said, how poor is this kid? He's got to be very poor that he doesn't even have... I remember Papa used to put cardboard in your soul when you got holes in your shoes, you know? Not even cardboard. It's just his feet are sticking out through the soles of his shoes. And I was placing the flag on him. And he was just an innocent bystander. He came to watch. And... And that would happen. You know, you never know when you were going to get hit. This is downtown L.A. And it was students that had gathered from various colleges and universities and they were marching. And this beautiful chick caught my eye.

SPEAKER_01:I think you date this in 72, right?

SPEAKER_00:Somewhere around there.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah. Yeah. And this one is actually a throwback. This went back to 1968. Yeah.

SPEAKER_00:This is the March on the Board of Education. This is the beginnings of the sittings on the Board of Education.

SPEAKER_01:Historically, this is when Sal Castro was removed as a teacher and there were efforts to retain him as a result of his being arrested for his participation in the blowouts along with 12 other Chicanos. the school board released him from employment. And then there were a series of actions to try to get him back. For example, you see the sign back there that says, retain Sal Castro Lincoln High. So this was the march towards the school board of education.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, now, if you look on the far left-hand side of the image, you'll see that bearded man with the dark shades?

SPEAKER_01:Yes, sir.

SPEAKER_00:That's Ed Bonilla.

SPEAKER_01:Ah, okay.

SPEAKER_00:That's the man who flips my worldview. He's the man who introduces me, says, bring your camera. And then in the middle, right behind the American flag is Alicia Sandoval. I believe that's her name, Alicia Sandoval. Oscar? Yes, yes, that is her. Okay, so she had a television program as well, and she was a school teacher, and she was extremely active. And the man in the front with the tie and suit is, Oscar, you remember his name?

SPEAKER_04:Yeah, his name was Vahak Marderosian.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, there you go. And he was head of the EICC, Educational Issues Coordinating Committee, which was organizing all these protests, education, and were negotiating with the Board of Education people, of which Julian Nava was a member of. So

SPEAKER_01:real quick. So for those of you that want documentary video evidence or information, there is a 32-minute video. put on by David Garcia called Requiem 29. And it deals with the inquest into the death of Reuven Salazar. An inquest is just a formal inquiry to decide whether he died by accident or whether he died at the hands of another. If they make a finding of died at the hands of the other, that normally, typically would lead to the filing of charges, sort of like a public grand jury as opposed to a private. And the finding of the inquest was that Reuven did die at the hands of another but no one was ever charged with that. So that's one video that you folks should look for and watch. The other is the Mexican-American civil rights story. And there is a one-hour segment called Taking Back Our Schools. I think Jesus Treviño was involved in the overall making of those four one-hour videos. And it deals largely with what happened during the blowouts and then the trial and then the sit-ins at the school board. You folks who are watching tonight's program have the benefit though of speaking to two people who were there during that time period and who actually recognize these people on a first name basis. Anyone else you recognize in these photos, either Oscar or Luis?

SPEAKER_00:Right behind, I can't see his face. I have other shots, which unfortunately I didn't send you. It is Father Luce, behind the young man next to the... Oh, I see his collar. Yeah, you see the collar? That's

SPEAKER_01:Father Luce. So Father Luis was with the Church of the Epiphany. How did you folks come to have a relationship with him enough to where he allowed you folks to use the church as sort of the headquarters for La

SPEAKER_00:Raza? That's a birthing process that starts with– they had– Father Luz had, with the Episcopalian Church, they had a social action program, which was national in scope. And Eliseo Risco, who was a field rep for the farm workers, had come into Los Angeles to do organizing on behalf of Cesar Chavez, who had met Father Luz. And so Father Luz then introduces Eliseo Risco, who is of Cuban background and Cuban immigrant who comes to the West Coast and is working in various different areas, but specifically with Cesar Chavez in terms of organizing. Eliseo comes into Los Angeles. He meets up with Father Luz, who gives him space. And then Father Luz brings up the idea of creating a newspaper, magazine for organizing. And then he brings in Ruth Robinson, who also works with the farm workers, and they begin with Benny Luna, who does the artwork for the first issues of La Raza, and then a host of other people that begin to come in to play, Moctezuma Esparza, Joe Raso, et cetera. A whole bunch of people start coming in, and that's the foundation, the beginnings of La Raza newspaper. You

SPEAKER_01:were not just limited to taking images of Chicanos. You and Oscar both have a body of work where you just go everywhere. This is in your home state.

SPEAKER_00:This is in my barrio, the South Bronx, and this is in the area of 139th Street between St. Ann's and Brook Avenue. I had met Young Lords who had come out to LA and on a number of trips that I had made back East, they invited me to hang out with them. So that's what I did, hang out with them. And there's several rolls of film that I took of the Young Lords. So was this a gathering, a meeting, a protest or? This was just a gathering of Young Lords, you know, just getting together or, you know, just cheering on the people and such like that. And this is also a young representative of the Young Lords who was selling the newspaper called Palante. And Huey Newton had just been released from jail and they put welcome back. So I captured this image of this woman young woman who is selling the newspapers and the backdrop just fits so appropriately to what and who she is. And it just... with all the other posters and images there. And she just stands out with the American flag with welcome back Huey and Palante. So you get this whole sense of Boricua and Black Panthers and US and all of these other things that are going on because it's a hippie shop. It's a smoke shop, which is where they're selling all of these posters. And it's a store with sensitivity. Homeboys.

SPEAKER_01:This is my favorite shot. When I was at North High School, I landed in Riverside in 78 in 10th grade, and I was lucky enough to take a Mexican-American studies class with a professor by the name of Richard Monguia. And one of the school books that they handed out in order for us to read, which is required reading, was the poem by Corky Gonzalez, Yo Soy Joaquin. And this photo. This photo graces the cover of that. And I've always loved this photograph. I, you know, the guy with the hat reminds me of my brother because that's how my brother wore his hat with attitude. It's like, don't mess with me.

SPEAKER_00:Well, this is, this is taken in the Aliso Pico projects. And again, it's just one of a whole series of shots because, you know, basically I'm a streetwalker. I'm a street photographer. I, I, whatever I'm surrounded with. And I do a lot of portraiture work. Now that I look back at my work, it's a lot of portraiture work. And the ability to capture an image such as Cesar Chavez. This is 1974 at the Biltmore Hotel, and it's a conference that's going on between the UAW and the United Farm Workers. And Cesar invited me up to the hotel room, and I'm just sitting across the bed from him, you know, just a couple of feet away from him. And so this is one, again, of several rolls of film and images that I took of him. The irony of this is that I was contacted by a friend at Time Life magazine who called me out of the blue to tell me, Luis, our photographer journalist cannot make the flight to LA and we got to get this story on Cesar. Are you willing to cover the event with Cesar Chavez? We'll get clearance for you. We can't supply you with film or anything else like that because it's too late. So can you? And I said, yeah, sure. Why not? So, I went, I met, I introduced myself to Cesar and his people. They brought me in and I hung out with them for that most of the day, capturing these images. I sent the film off to New York to Time Life and then within a short time afterwards, they said, they returned everything to me and they said, we're not running the story.

SPEAKER_02:So

SPEAKER_00:I said, okay, fine. And so it remained in my archive all of this time. This is Rodriguez. I forgot her first name. This is at the January 31st. That's Rosalía Muñoz. And in the background on the walkie-talkie is Esteban Torres. Celia Luna Rodriguez, that's her name. Celia Luna Rodriguez. She was a major organizer against police brutality. And so that's where that photograph was taken. And again, there's just... you know, half a dozen more.

SPEAKER_01:So you traveled the world. So you weren't just a Chicano photographer in California or a photographer in your hometown. You actually went other places in the world.

SPEAKER_00:This is Budapest, Hungary, and this is El Maestro David Alfaro Siqueiros. And The image got printed, and actually the exhibition, Cicadas in L.A., Censorship Defied, came about because of these photographic images when people asked me, what the hell were you doing in Budapest, Hungary in 1971? And so as I told them the story, they said, you've got to write this down. You've got to do something with it. Out of these images came the exhibition, my first exhibition, curated exhibition at the Orchard Museum. But the way I got there, the way I got there is interesting because it comes about through the man who is now deceased, the Peace Action Committee, who comes into La Raza saying we'd like a representative to attend the US delegation to Budapest, Hungary and the World Peace Conference. And everybody else was caught up with the Police trials and everything else like that. So I volunteered and I wind up in Budapest, Hungary. And Siqueiros, when he hears that there's a Chicano in the American delegation, he calls for a meeting and he says, Compañero, cuéntame de este movimiento Chicano. And he sits me down between himself and his wife, Angelica, here, Angelica Arinal, who we're saying goodbye. She's getting into this little Volkswagen and she turns to me and she says, Luis.

UNKNOWN:Luis.

SPEAKER_00:Como dicen ustedes, Chicana power. I can't believe you, Mexiqueros. I can't believe it either because it's, again, it's fate. It's karma. And I truly believe that many of the things that I've become involved with, there's a purpose. There's a predestiny that I never knew that I had. Los dioses mandan. Exactly.

SPEAKER_01:So, Oscar, so you saw yourself as just a photographer. You were paying for everything out of pocket. What were your target images?

SPEAKER_04:At what point? What do you mean?

SPEAKER_01:So now the moratorium is over, you know, there's a variety of different things going on. Do you continue in that vein of photography, of protests in 71 and 72, or do you now branch off to other things, or is that the time period that you go to Texas?

SPEAKER_04:No, I had already been to Crystal City. And by the mid-70s, well, I was looking to document a broader part of the Hispanic or Chicano community. And so I started doing cultural events and just people in general. I did many topics and themes, but as a photographer, I also did urban scapes, study of the environment, the city. And as a matter of fact, the Smithsonian has some of my photographs where I documented... urban renewal. Some of my photographs from a series that I was doing in the 70s, they were used in a book which the Smithsonian also sponsored. It was based on a book called These Mean Streets. And they did an exhibit at the Smithsonian and was later went to the Museo del Barro in New York. So, you know, my images have, have kind of taken on a life of their own. I mean, we talk about my archives on one hand, but my active things on the other hand. So I got involved with the business community. I was doing stuff for, you know, to make money. Chamber of Commerce is on that. But I think if you're... A lot of my images have been used,

SPEAKER_02:for

SPEAKER_04:instance, a very well-known lecturer, Gregorio Luc. He and I collaborated on an exhibit, which was, we titled El Movimiento and Beyond. And that kind of a philosophy where, yes, I mean, the movimiento is important, but myself, I need to do a little bit more, you know, a little bit more upscale stuff, a little bit more positive stuff. So I try to document cheerful things, you know, things that people would say, hell yeah, that's something that reminds me, they could remind them of something they've done or something they enjoy. So I like to do positive things. And I sent you some images of cultural things. And I worked a lot with artists, like with the Gómez Art Gallery, with Mexicano Art Center, and have exhibited with many artists. I've become friends with many artists, like Los Four, very well-known artists. I became friends with a very dear lady, Josefina Quesada, who was also studied with Siquieros. And she came up here to work on restoring his mural, América Tropical. So we became dear friends and I, you know, I have a series of artists that I've documented over the years and I'm, she being one of them, but different artists that are, you know, like Asko and Almaraz and Frank Romero and and dancers, musicians. So I like to do up things, you know, besides the negative, a few negative things, but I like to do upscale things.

SPEAKER_01:Well, I think that documenting everything life, everyday life, I think is important. Yeah,

SPEAKER_04:I think you shared a word with me, which I forgot. You said something about anthropological something. You called it, you gave it a name, which was kind of interesting

SPEAKER_01:i call it it's not a pictorial ethnography is how i call it okay

SPEAKER_00:yes absolutely absolutely let me interject just a moment here i want to thank oscar for bringing up josefina quesada's name she's very important to the conservation and the return to public view of cicadas mural america tropical The story behind her. And again, these are the stories that are so important because photographically what Oscar and I are doing and a number of others consciously, even more so now, is documenting a background history of people who have never been given their recognition or their due. within the larger circle of the cultural explorations and developments that we've been going through over these years and decades and centuries. And Josefina was anointed, appointed by David Alzaparo Siqueiros to go and look at the mural of America Tropical and to give him a report, a condition report. because the first efforts to conserve the mural was being done through Schiffer Goldman and Plaza de la Raza and a host of people from our community to conserve the mural. And so the first efforts to conserve the mural come out of our community. It doesn't come out of the Getty. It comes out of our community and it's a long, long struggle. So Josefina, goes back and forth and reports to Siqueiros on the condition. And then eventually she comes to live here in Los Angeles, and Oscar meets her, I meet her, and she becomes part of the mural movement here in Los Angeles. And she becomes a vibrant part of the muralist movement within our community. She works with people from Spark. She works with Judy Baca, with any number of artistas in doing mural work. And her murals still stand in different parts of Los Angeles. So It's important to note, because the conservation and the eventual presentation of America Tropical at Olvera Street starts with Josefina Quesada coming into Los Angeles. Y es una mujer del pueblo, heart and soul. And you've got to give that recognition to those people that have never received it. Punto.

SPEAKER_02:Right.

SPEAKER_01:So, you know, it's... If you believe it, it's 7.51. And I remember when we got together for our first phone chat, there was a fear that we wouldn't have enough to talk about. And here we are, 10 minutes till 8. And we still haven't talked about or shared Oscar's images from Texas or the images of 18th Street. I looked at his catalog at the UCLA. He's got Acción. He's got Daniel Valdez. He's got Bobby Espinosa. I mean, Oscar's work is on display. We haven't talked about what publications you folks have for sale. We're going to get to that before we end. Somebody asked for the songs that I played. I played Yo Soy Chicano by Los Alvarado. Cubo Raza by Agustin Lira and Patricia Wells Solorzano. Brown Eyed Children of the Sun, that was Daniel Valdez off of the Mestizo album. I want to invite Ophelia Valdez to come and give us a chat because this is done in conjunction with Cause Connect and with the Riverside Art Museum and the Cheech. So I'd like to invite Ophelia to give us a little chat. Ophelia. Welcome, nice to see you again.

SPEAKER_03:Buenas noches, thank you so much. And to your speakers, it's an honor. I'm old enough to have been around during that time, so it's... Very touching, all that I've heard this evening. My part tonight is to remind everyone about the Cheech, something that I am hopeful, Luis and Oscar, that we can convince you to bring, maybe develop an exhibit about. as soon as we can and bring it to the chief. That's what it's all about. And just to give an update, some of you already have this information, but for those of you who don't, everything is moving forward. We have found a contractor that's going through the city. The final agreements have to be approved by the city council. And we're very hopeful that that will be done this fall. Also, for those of you who know anyone, I'm sure you do, we will soon be recruiting for the Cheech subject matter expert curator. We're very excited about that. Finally, the Cheech will have its own curator. And we're pleased to announce that Union Pacific has awarded us$15,000 to go for programming at the Cheech. And if anybody would like to continue to donate at any level, we invite you to text 44321. and enter Cheech. Very excited about that. And finally, I just wanted to show you the latest that we have in this time of the coronavirus. We have our own beach mask that you can order through the museum, www.riversideartmuseum.org slash the Cheech store. And if you follow our assemblymen, Jose Medina, who is responsible for$10.7 million that came to the Cheech. He is wearing it. And with the bill that is sure to pass for ethnic studies, his colleagues are also wearing them. So the Cheech is getting around everywhere. I invite all of you, if you have any questions, please give us a call, contact the museum. And thank you again to our speakers. It's been a thrill. Thank

SPEAKER_01:you. Thank you. So somebody wanted to thank you for mentioning Chicanas. There was one that wanted to know what's going to be the name of the Cheech Museum. It's going to be the Cheech Marine Center for Chicano Art, Culture, and Industry. And people are asking if there's going to be a part two to this discussion. I am open to that, depending on schedules. Oscar, you have a public that is available for purchase. And what is the name of that publication?

SPEAKER_04:Well, the publication is the Oscar Castillo Papers and Photograph Collection. And it's available through UCLA or on Amazon. And it's an oral history, which was done by Elise Mazzadiego, edited by Colin Kessler. I can't think of his name right now. Colin Grunkle, I'm sorry. And through John Noriega and the Chicano Studies Library. But here's a picture of it. And I really enjoyed working with the Chicano Studies Library. And we got five or six scholars and my friends who wrote. That's one of the things I like about my photographs is I enjoy when they inspire people to write and some people have chosen some of my photographs and written about them or some people have just written about their you know their their our friendship or what they knew about me so it's I recommend it and I hope you can at some point I'd like to have it at the Cheech for sale there at the Cheech too if it's available

SPEAKER_01:I'm sorry We'll definitely work that one out. Luis, do you have any publications for sale, sir?